Strategies for Navigating the Music Education Major for Incoming and Transfer Students

By Phillip Payne (Kansas State University); Natalie Royston (Iowa State University); Adrian Barnes (Rowan University); Kate Bertelli-Wilinski (University of Colorado)

Keywords: Transfer, University Credit, Music Teacher Education, Attrition and Retention

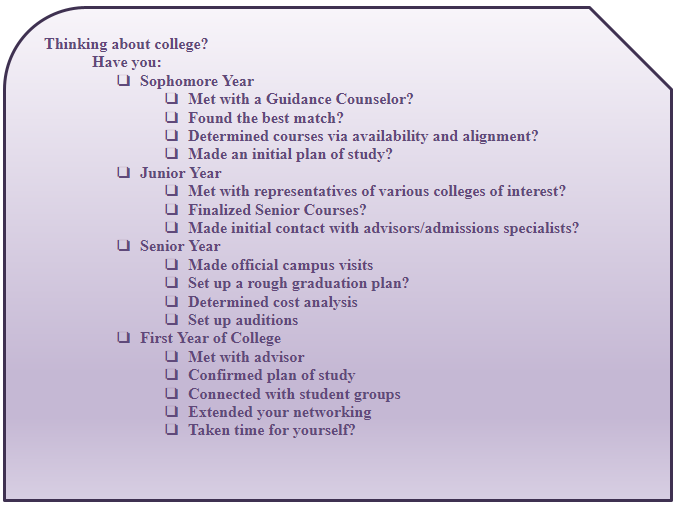

As students from across the country prepare to enter college, it is important that they understand the process from career planning to enrollment. Given the enormity of a student’s decision regarding which school to attend, the teacher’s task of providing advice for these students is almost as tenuous. Teachers who are more knowledgeable about admissions systems and processes for both universities and music programs may be better equipped to help their students prepare for and navigate the transition into a higher education institution.

Currently, there is a general lack of resources that provide music teachers with details about the personal, social, and academic rigors that lie ahead for music education students. Additionally, few resources discuss the various school-related factors that music education students should consider when making decisions about their future careers. As based on the findings of previous research, this article serves to fill a gap by providing two vital perspectives involved in making the decision to attend a specific school: the student and the college. The included resources address three areas that are most concerning for music education students, as well as three school-related factors that can impact a student once their choice to attend, has been made.

Student Perspectives

Academic

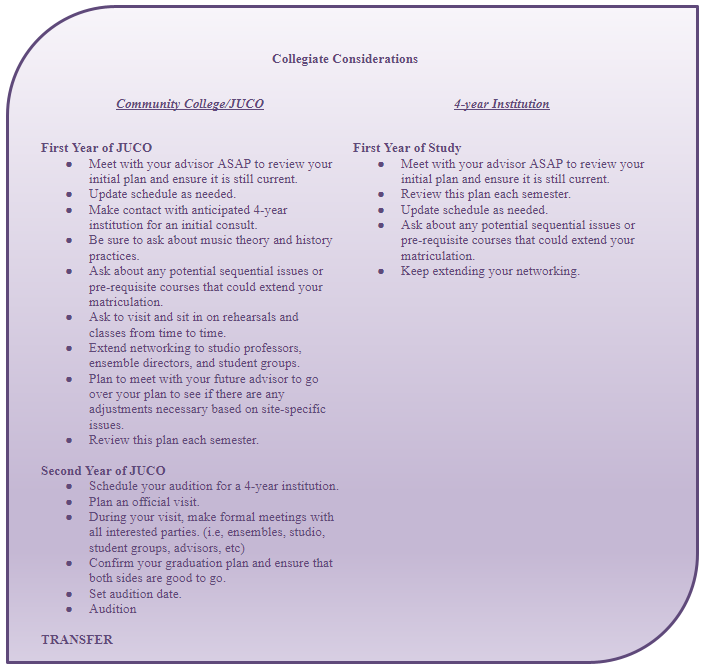

Students’ concerns about moving to a new institution, be it a two or four-year institution, can be understood as an academic, social, or personal issue. Struggles related to academic issues include difficulties with coursework, routines or procedures of specific faculty or misunderstandings related to the music education curriculum. Many times, these issues result in increased course-load and/or additional semesters that lead to elevated stress both socially and financially. Students also frequently express their frustration with the current system as they continue to be confused by their school’s requirements. These struggles suggest that continued guidance and support are essential at this pivotal moment in the transition process.

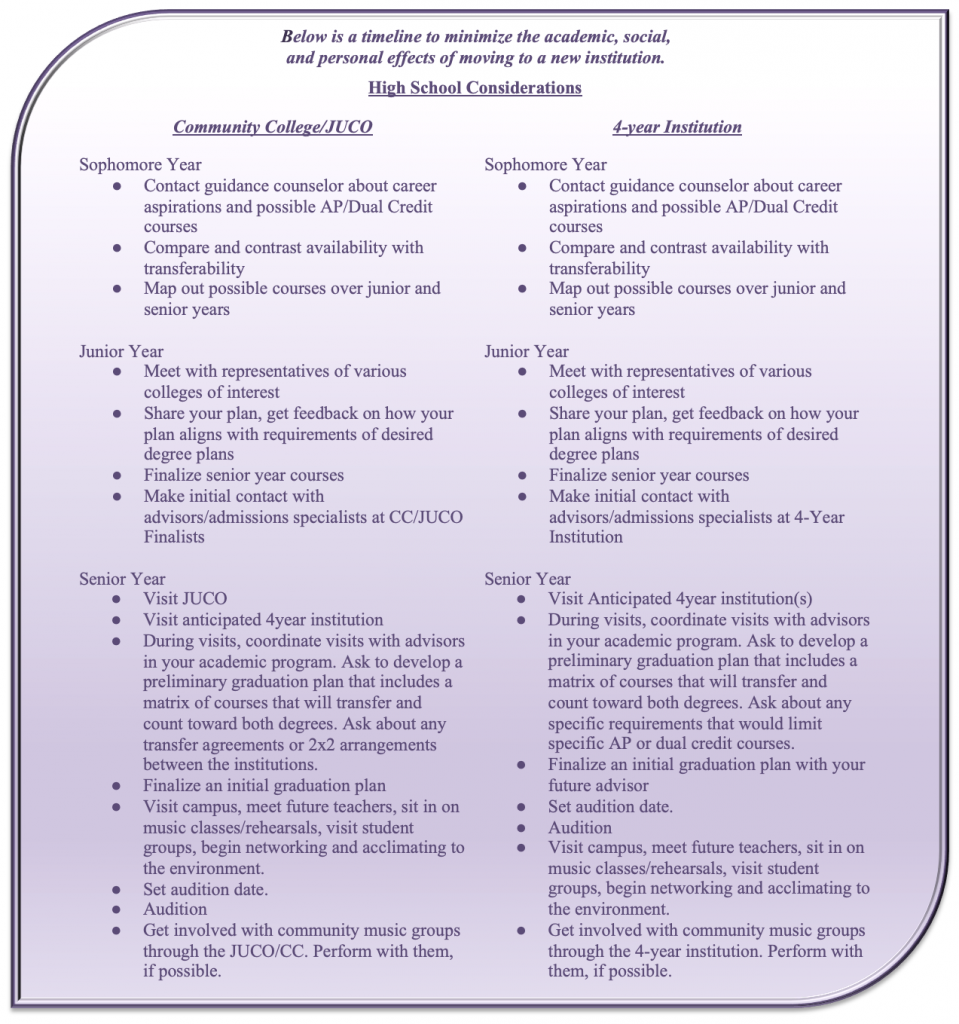

Given the high mobility rate of students[1] and the increased popularity of AP and Dual-Credit courses, having an easily accessible matrix of courses that are mutually accepted and applied could be an asset to freshmen and transfer students. While high school counselors and advisors serve as the initial point of contact, their advising often focuses on general college admission. A music educator might be better able to address topics related to majoring in music given their personal experiences and current contacts with collegiate music educators.

Social

The importance of the social aspect of starting at a new school cannot be overstated. Becoming a part of the new community is important and can create a sense of belonging, comfort, and security. However, some new students have difficulty establishing a social circle in the college environment. Most students realize it takes time to establish these bonds but is often unsure of how to adequately navigate this new environment. This may be especially true for transfer students due to their age and year in school. To help students connect with social circles, it may be worthwhile to encourage early on-campus visits as well as immediate participation in student groups and organizations. Primary contact at the university who can answer all music-related questions and moderate all conversations may also help students become acclimated. Music education and college life allow for multiple opportunities to connect with others; music educators can play a pivotal role in bringing students’ attention to various options.

Personal

Incoming students often face lost or empty credits because the higher education institution does not deem them applicable to their degree requirements. High school Advanced Placement (AP) Exams and dual-credit college courses are often suspect to aiding the student. Institutions vary in their acceptance of AP exam results (some only use the results to determine course placement)[2] and occasionally cap the number of credits accepted. Because these credits do not always meet specific degree requirements,[3] students can experience unrestricted electives, excess credit hours, and no time saved in earning the degree. Transfer students (and occasionally new students) frequently experience issues with the transferability of courses (or lack thereof) and sequential course scheduling. These students are often surprised with how these factors can affect their graduation timeline and, relatedly, their personal affairs.

An unintended consequence of these extra, empty hours can be the student’s ability to receive financial aid. With federal financial aid rules[i], extra course credits applied to the degree can result in both a credit overage and loss of financial aid,[ii] usually just prior to degree completion.[iii] These financial aid rules may greatly impact transfer students. With the rising nature of college tuition, the affordability of two-year institutions, and uncontrollable life changes, it is safe to assume that the pathway to the music education degree will not always be direct. Therefore, the ability to transfer credit has become one of the most important aspects for some students, especially for those choosing to initially attend a community college. To help the situation, students should first meet with a trusted university advisor to learn how the course evaluation process works, then thoroughly research the transferability of all courses and degree plan requirements before enrolling in courses. Stakeholders could help students by reminding them to monitor institution requirements, transfer articulation agreements, AP courses, and/or dual-credit courses. Such assist is essential for ensuring a successful transition from one school to the next. Additionally, music teachers could create and maintain an index of music education faculty or advisors in the region that could serve as points of contact for prospective students.

Considerations for School Selection

Audition

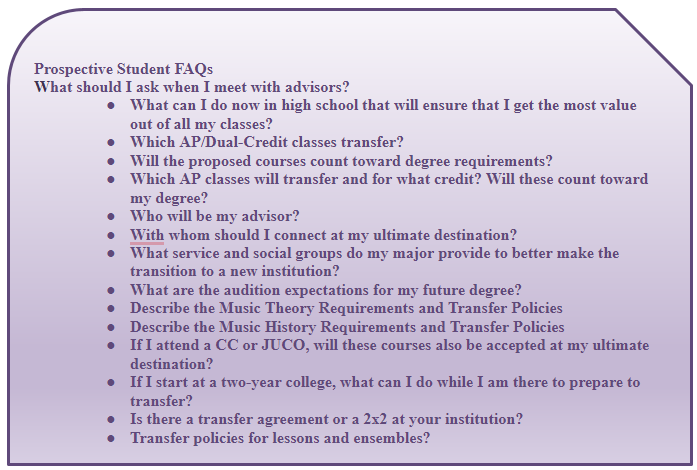

When considering enrollment in a higher education institution, students’ decisions should be greatly impacted by the music department’s audition policies, curriculum, transparency, and networking ability. Particularly, the alignment of these considerations and student perspectives is critical (see high school considerations checklist above). The primary focus for most new music students remains the audition. For many students, the thought of auditioning can cause anxiety and nervousness; they often question their ability to measure up to standards set by a collegiate music department. As a result, auditioning can immensely impact students’ social and personal standing before their first day as an official student. Before students prepare to attend an audition day at a university, every effort should be made to identify the specific audition criteria (i.e., prepared literature, scales, sight-reading, etc.) for who and what they are auditioning (admission, scholarships, etc.), and the level to which they are expected to perform. Students should reach out to their prospective schools to inquire about the day proceedings and other expectations beyond performing on their primary instrument–e.g., theory and piano placement exams, music education interviews, etc. High school music teachers can be central to preparing students musically, academically, and emotionally for audition day. By preparing and empowering the students to ask about these items prior to audition day, students will have a greater sense of readiness and hopefully lower their level of anxiety going into the audition. In addition to preparing students for a successful audition, directors can also reinforce the concept that the audition is just another step in reaching their music education goals.

Curriculum

The curriculum often comprises a large source of anxiety for first-time and transfer students. These stressors include understanding the frequency and rotation of course offerings as well as the specific requirements to attain the degree. In an effort to address this concern, colleges should always be able to provide current and future students detailed, updated, and transparent degree plans with information about when and how often courses are offered, what exactly is required for the degree, and what substitutions are allowable, including any articulation agreements with community colleges. If high school music teachers and counselors can readily access this information, they will be better able to advise or provide these resources more efficiently to their own students.

The greatest help would come from maintaining a shortlist of contacts who will provide excellent advice in this momentous decision for these young, new, and naive music education majors. Sharing these contacts with students could add clarity, accessibility, and understanding to a very complex process. However, with the sheer number of variables and students to consider, public school or community college professors may consider it an onerous task to speak with each individual student.

Therefore, we have also designed a list of FAQs for students to take with them on-campus visits that directly address these issues (see Prospective Student FAQs above). This resource includes questions regarding classes, barriers, the audition, and transfer courses, among others that will aid in providing additional transparency.

Networking

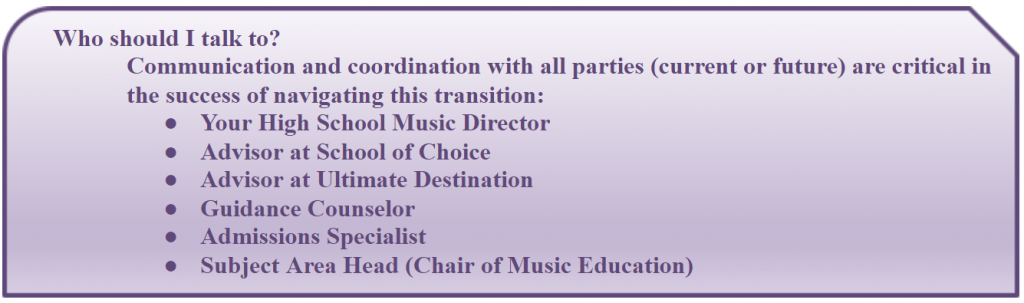

Networking can assist students in the successful pursuit and completion of collegiate degrees. A network is most beneficial when it includes all stakeholders and emerges from the focus on a student’s success in a given curriculum. As with all successful ventures, communication remains the primary component in ensuring a student’s success.

One idea to address communication-based issues is for music teachers to invite college music representatives and other potential stakeholders to visit prospective students and to share experiences, advice, and details for navigating the enrollment process (see Who should I talk to?).

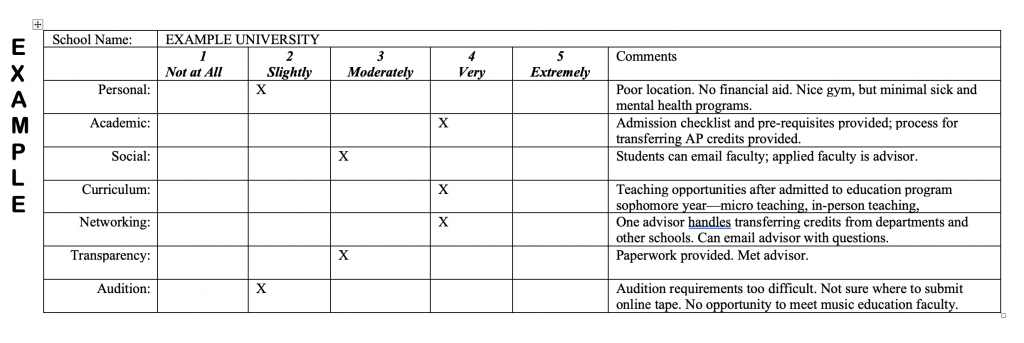

Such a meeting could help students make critical decisions about course enrollment by understanding the timing of their decisions and relevant details about the variables involved. This networking could ultimately save students multiple semesters of tuition and fees as well as contribute to their personal, academic, and social well-being. Given the multiple options available to future collegiate music students, the complexity of the process, and the importance of transparency, we designed a comprehensive rating scale encompassing the areas listed above to assist students and assist them in determining their best ‘fit’ (see College Considerations).

Conclusion

Considering the pressure on high schoolers for an early onset of their career paths, empowering students to chase their passion of studying music is a critical part of bolstering our profession. These students encounter many stressors beyond the audition process that extend into personal, social, and academic areas of their lives.[4] Given the impact of music teachers on a student’s choice to pursue music teaching as a career,[5] these individuals can help smooth the transition process by actively pursuing knowledge and resources related to institution enrollment. Specifically, acquired resources should enhance students’ ability to select a future school that ensures their academic, social, and personal success. The earlier that mentors reach out to prospective students, the higher the probability of increased success for the profession. By stakeholders becoming involved in the enrollment process, newly arriving students can better establish a sense of community and self-efficacy within their respective music education programs. Moreover, working more closely and developing strong relationships between colleges and PK-12 teachers can only strengthen our field. It is our hope that the provided strategies, resources, and checklists (See the checklists and questions above) can better serve all students regardless of their path to the music classroom.

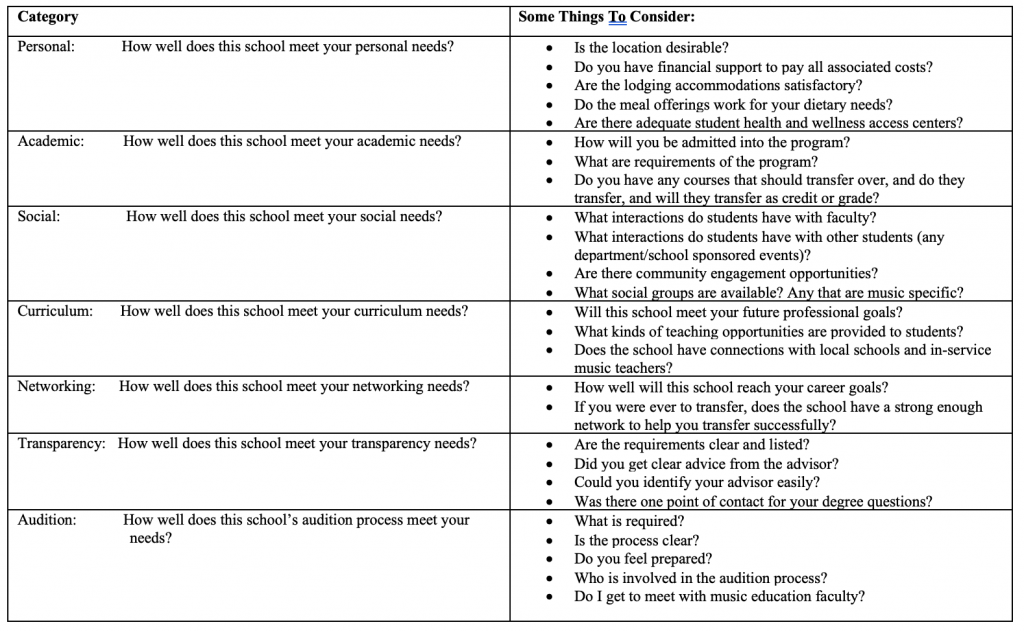

School Selection Rating Scale

As you prepare to select a school, you may experience a wave of emotions, connect with a lot of people, and at times feel overwhelmed. We designed the tool below to help you collect your thoughts and to document your initial reactions to campus visits, interactions with campus individuals, and overall comfort with a program.

Directions: Rate each of the seven categories below (personal, academic, social, curriculum, networking, transparency, audition) depending on how well the school meets your needs. Consider some of the example questions and topics below when making your rating choice. Note that you should also create your own questions and topics to consider based on what is most important to you. Use the comments section on the rubric to support your rating and to capture your thoughts about the overall experience. You should complete one full rubric for each prospective school. Once completed for each prospective school, use the ratings and the comments to compare schools and identify the one that you feel would be best for you.

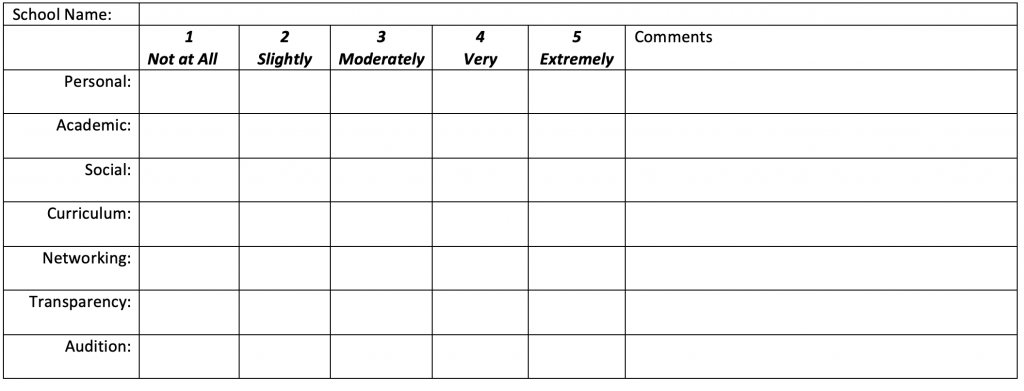

School Selection Rating Scale Template

Directions: Rate each of the seven categories below (personal, academic, social, curriculum, networking, transparency, audition) depending on how well the school meets your needs. Consider some of the example questions and topics below when making your rating choice. Note that you should also create your own questions and topics to consider based on what is most important to you. Use the comments section on the rubric to support your rating and to capture your thoughts about the overall experience. You should complete one full rubric for each prospective school. Once completed for each prospective school, use the ratings and the comments to compare schools and identify the one that you feel would be best for you.

[1] Don Hossler, Doug Shapiro, and Afet Dundar, “Transfer and Mobility: A National View of Student Movement in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2011 Cohort.” National Student Clearinghouse Research Center [2012], https://nscresearchcenter.org/signaturereport15/ [accessed January 11, 2020].

[2] Halle Edwards, “These Are the 5 Worst Problems with College Board’s AP Program,” Prep Scholar Blog, entry posted May 1, 2018, https://blog.prepscholar.com/the-5-worst-problems-with-college-board-ap-program [accessed January 11, 2020].

[3] Paul Weinstein, Jr., “Diminishing Credit: How Colleges and Universities Restrict the Use of Advanced Placement” Progressive Policy Institute, entry posted September 8, 2016, https://www.progressivepolicy.org/issues/diminishing-credit-colleges-universities-restrict-use-advanced-placement/

[4] Natalie Royston, Phillip Payne, Adrian Barnes, & Kate Bertelli-Wilinski (in press). “An Examination of Student and Faculty Perceptions Regarding Music Education Transfer Students’ Preparedness and Experiences.” Research and Issues in Music Education.

[5] Ann Porter, Phillip Payne, Frederick Burrack, & William Fredrickson, “Encouraging Students to Consider Music Education as a Future Profession” Journal of Music Teacher Education [2016], DOI: 10.1177/1057083715619963

About the Authors

Dr. Phillip D. Payne is an Associate Professor and Chair of Music Education at Kansas State University, specializing in Instrumental Music Education. His duties at K-State include Lead Advisor for Music Education Majors, teaching undergraduate and graduate classes in music education, and supervising student teachers. Dr. Payne holds Bachelor of Music Education and Master of Music degrees from Southwestern Oklahoma State University. He also holds a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Music Education with an emphasis in Instrumental Conducting from the University of Oklahoma. His research interests include assessment in music education, technology integration, music teacher recruiting and retention, personality and instrument choice, modern band pedagogies for the music classroom. Publications include chapters in Applying Model Cornerstone Assessments in K-12 Music, Teaching Music through Performance in Band, and Developing and Applying Assessments in the Music Classroom, as well as articles in Journal of Music Teacher Education, Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, and Music Educators Journal. He is currently the Chair of NAfME’s Assessment SRIG, Co-Facilitator of SMTE’s Program Admissions, Assessment, and Alignment ASPA, and Chair of the Research Caucus for KMEA. He serves as an adjudicator, clinician, and guest conductor throughout the Midwestern United States and is an active member of The National Association for Music Education, Society of Music Teacher Education, and Kansas Music Educators Association.

Dr. Natalie Steele Royston is Associate Professor and Coordinator of Music Education at Iowa State University. Prior to her current appointment, Dr. Royston served with the Iowa State University bands as Associate Director of Bands, Director of the Cyclone Marching Band, director of the basketball Pep Band, and conductor of the Concert Band. Previously, she served as Associate Director of Bands at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas, and taught in the public schools of Ohio. Dr. Royston received a Bachelor of Music Education degree and Master of Music degrees in Trombone Performance and Wind Conducting from Ohio University and a Ph.D. in Music Education from the University of North Texas. She is an active adjudicator, clinician, and researcher. She has presented at conferences and research symposiums across the country, including at the Midwest Band and Orchestra Clinic. She is also published in the Journal of Research in Music Education, the Journal of Music Teacher Education, Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, Research and Issues in Music Education, Contributions to Music Education, the Music Educators Journal, and the Instrumentalist as well as several state music education journals.

Dr. Adrian D. Barnes is an Assistant Professor and co-coordinator of Music Education at Rowan University. He began his teaching career in a Title I school in Bradenton, Florida, as a band and orchestra director. While in Florida, he served as an assistant director of marching band at Southeast High School, working specifically with drum-line. Dr. Barnes has worked closely with students from historically marginalized communities, as well as neurodivergent learners. While attending Texas Tech University, Dr. Barnes served as a research assistant on a Promise Neighborhood Grant working in the historic Paul Lawrence Dunbar Neighborhood of East Lubbock, Texas, a predominantly Black and Latinx community. Dr. Barnes’s research interests include collegiate pathway programs that increase the representation of historically marginalized populations into 4-year intuitions of higher education (IHEs) institutional agency and outreach in historically marginalized communities, and the recruitment practices used to recruit Black and Latinx students by music educators at minority-serving institutions.

Dr. Kate M Bertelli-Wilinski is a music educator and researcher with a background in both choral and instrumental music. Over the years, she has taught students in a variety of age groups within K-12 and higher education. Dr. Bertelli holds a Bachelor of Arts degree with dual concentrations in music and legal studies from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, a Master of Science degree in (music) education from Troy University, and recently earned a Ph.D. in music education from the University of Colorado Boulder. Her doctoral dissertation, Choral Voicing in Secondary School Ensemble: Teacher Perceptions and Procedural Evaluation, centered around part assignment procedures in the high school choral classroom. While at CU Boulder, Dr. Bertelli served as a part-time graduate instructor, where her duties included teaching undergraduate courses, supervising student teachers, assisting with faculty research studies, and managing various administrative databases. Dr. Bertelli has presented her research at several state and national conferences and symposia dedicated to music education. She currently serves on the Advisory Committee for the Music Educator’s Journal and has been a peer reviewer for the American Educational Research Association. Dr. Bertelli’s research interests include teacher certification, professional development, teacher evaluation, transient students and teachers, and voice classification. She is a participating member of The National Association for Music Education, the Society of Music Teacher Education, the International Society for Music Education, and the American Educational Research Association.